Chance and Modernism: How Surrealists and Dadaists Represented Play and Randomness

During the early 20th century, the emergence of surrealism and Dadaism marked a radical departure from traditional forms of artistic expression. Both movements revolved around the idea of breaking free from rational control, embracing randomness, and finding deeper meaning in chance. Central to their aesthetic and philosophy was the notion of play—play of the subconscious, of language, and of materials. Artists like Marcel Duchamp, Max Ernst, and André Breton explored these themes in innovative ways, drawing direct parallels between the artistic process and games such as chess, card games, and roulette. This article explores how their work reflects these ideas, showing the philosophical significance of randomness in modernist art.

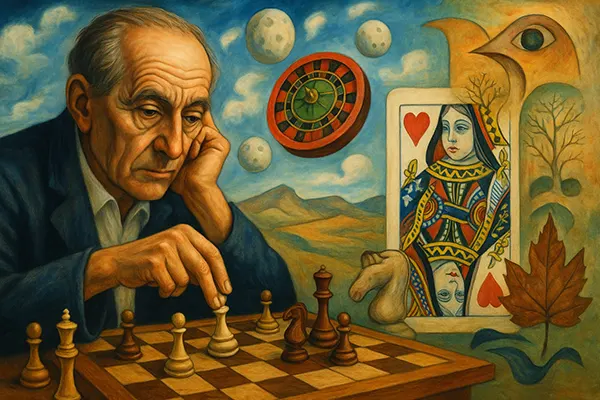

Games of the Mind: The Chess of Marcel Duchamp

Marcel Duchamp’s obsession with chess wasn’t just a personal hobby—it became an artistic and intellectual pursuit that reflected his philosophy on chance and control. Duchamp, a key figure of both Dada and surrealism, often used chess as a metaphor for life, creativity, and the movement of ideas. Unlike games of pure chance, chess is a structured system, but Duchamp infused it with unpredictability by intertwining it with art. His 1917 piece “Portrait of Chess Players” and the installation “Pocket Chess Set” bridged the gap between game and artwork, treating the strategic interplay as a kind of performative creation.

Duchamp’s later abandonment of conventional art to focus on chess was symbolic. To him, the game represented a higher form of thought—pure, abstract, and uncorrupted by the art market or critical opinion. Even his famous readymade “3 Standard Stoppages” (1913–14), where he dropped threads from a height and mounted their random curves, echoed the same fascination with rules disrupted by chance. This piece offered a blueprint of how irrationality could be captured and framed without being entirely uncontrolled.

In Duchamp’s worldview, randomness was not an escape from form but a new way to define it. His use of chess both parodied and celebrated systems of control, making the game a tool for exploring the boundaries between determinism and freedom. The logic of the board became a canvas where disorder gained legitimacy.

Chance as Artistic Medium in Duchamp’s Practice

“3 Standard Stoppages” remains one of the most eloquent demonstrations of how Duchamp allowed randomness into his artistic method. By letting threads fall naturally and preserving their curves, he broke with traditional measurement systems. He once claimed it was “a joke about the meter,” yet it questioned the very foundation of objective truth in visual representation.

This gesture—simple in action but radical in meaning—turned arbitrary movements into sacred lines. By preserving their form, Duchamp elevated chance to the level of aesthetic law. It showed that even randomness, when acknowledged and repeated, gains a form of structure and narrative. This underpins much of modernist experimentation.

Duchamp’s work thus transformed the passive concept of ‘luck’ into an active, integral method of creation. Chance was no longer a background condition—it was foregrounded, manipulated, and interrogated as part of the conceptual process.

Visual Automatism and Game in Max Ernst’s Collage Worlds

Max Ernst, another key figure in the surrealist and Dadaist movements, brought games of chance into his artistic practice through collage, frottage, and decalcomania. These techniques were designed to bypass conscious intention and embrace the unexpected. Collage, in particular, functioned like a card game—cut, shuffled, and recombined images leading to unpredictable narratives and visuals.

Ernst’s 1920s collages such as *Une semaine de bonté* (“A Week of Kindness”) brought absurd juxtapositions into formal settings, mimicking the effect of placing a wild card into a rational deck. This randomness, however, was not without meaning. It questioned the logic of traditional iconography and narrative by confronting viewers with new visual grammars born of spontaneous association.

In Ernst’s case, games were not only metaphors but also mechanisms. His use of frottage (rubbing pencil across textured surfaces) mirrored the act of casting dice or spinning a roulette wheel—actions where control is ceded to materials or environment. From these impressions, new forms emerged that Ernst interpreted and developed further, making the unconscious a collaborator.

The Role of the Irrational in Ernst’s Techniques

Ernst’s visual methods formalised the irrational. While at first they appear haphazard, they became rituals for generating meaning through indirect paths. Frottage and collage mimicked randomised systems, yet Ernst framed them deliberately within a compositional context. In this, there’s a tension between chaos and order that parallels the structure of gambling games—rules exist, but outcomes are uncertain.

This ambiguity allowed Ernst to engage deeply with surrealism’s core idea: accessing the subconscious. Just as a roulette wheel spins beyond the player’s control, so too do Ernst’s materials evolve beyond the artist’s foreknowledge. Yet, he remained the interpreter—ordering the random into coherent statements.

Ernst’s artworks challenge the myth of artistic genius as pure control. Instead, he proposes a genius willing to surrender, to lose the game, and in doing so, find something unexpected and authentic. This model resonates strongly with the surrealist ethos of embracing the irrational as truth-bearing.

André Breton and the Poetics of Card Play

André Breton, the founder of surrealism, brought literary and psychological dimensions to the discussion of play and randomness. His fascination with games extended to card playing, especially tarot, which he saw not as divination but as poetic randomness—a method to unlock hidden truths from the psyche. His writings, especially *Nadja* and *Mad Love*, blend narrative with the logic of dream and chance.

In “The Manifesto of Surrealism” (1924), Breton stated that pure psychic automatism was the path to true expression. To achieve this, one must remove intention—an idea that echoes the dealing of shuffled cards or the spin of a roulette wheel. Breton considered these devices as tools to disrupt rationality and provoke revelation, not amusement alone.

In the 1930s, surrealist gatherings often included invented games, from “exquisite corpse” drawings to symbolic charades. These activities were designed not only to entertain but to rewire perception, to allow the subconscious and chance to speak in collective rituals. For Breton, play was not trivial—it was transformative and necessary.

Symbolism and Semiotics in Surrealist Games

The symbolism of cards in Breton’s thought extended beyond fortune-telling. Cards represented the interplay of fate and personal will, mirroring his philosophical stance on life and creativity. Each card drawn became a prompt for language, emotion, or action. The reading process was as much performance as reflection.

This aligns closely with semiotics in modern art, where signs don’t have fixed meanings. Just as a joker can shift the meaning of a game, surrealist symbols mutate based on context and intuition. Games enabled such mutations, making them ideal for poetic exploration.

Breton’s commitment to randomness was a refusal of authoritarian logic. By endorsing games as creative devices, he argued for a new kind of knowledge—not scientific, but experiential, fragmentary, and emotional. This was a form of learning where losing control was the point.